Back straight or bent over: What's the RIGHT WAY to lift something up?

Summary:

There is no one-size-fits-all way to lift: The “back straight, lift with your legs” advice isn’t wrong, but it’s not universally ideal. Research shows that different lifting styles (stoop, squat, and freestyle) impose different types of stress on the spine, and the best choice depends on your unique physical condition and injury history.

Different lifting styles load the spine differently:

Squat lifting = highest compressive loads

Stoop lifting = highest shear loads

Freestyle lifting = highest total loads

These forces can influence injury risk depending on conditions like disc herniation, osteoporosis, or spinal stenosis.

Injury-specific recommendations matter:

Disc issues or spondylolisthesis? Favor squat lifting to reduce shear.

Osteoporosis or compression-sensitive spines? Favor stoop lifting to reduce compression.

No injury? Use any lifting style, and prioritize variety to reduce overuse.

Trust your body’s instinctive movement:

According to Dynamic Systems Theory, your brain self-organizes the best movement strategy based on available inputs (e.g., strength, flexibility, fatigue). Rather than rigidly following external rules, your body often selects the most efficient path for the task at hand.

Read the whole article below:

Back straight or bent over? Whether we’re 8 or 85, we’ve all heard the same advice when it comes to lifting something up off the ground: “Keep your back straight! Lift with your legs!” Why is it so common? It comes from the idea that bending over and lifting (flexing the spine under load) may result in low back pain or injury. And, it might. However, is that true all of the time?

Is bending your knees and keeping your “back straight” always the safest and most efficient way?

Well, the answer lies a bit deeper into understanding biomechanics and motor control, but an excellent study by Von Arx et al. (2021) examines three different lifting postures:

Stoop lifting: You bend over at the waist to pick something up with a flexed spine

Squat lifting: Aka the “right” way to lift, where the back is kept straight and you use lower body to help lift

Freestyle lifting: Essentially a combination of both. See pictures below (Figure 1).

(Figure 1)

Before we get into the results of the study, let’s talk a little bit about back pain.

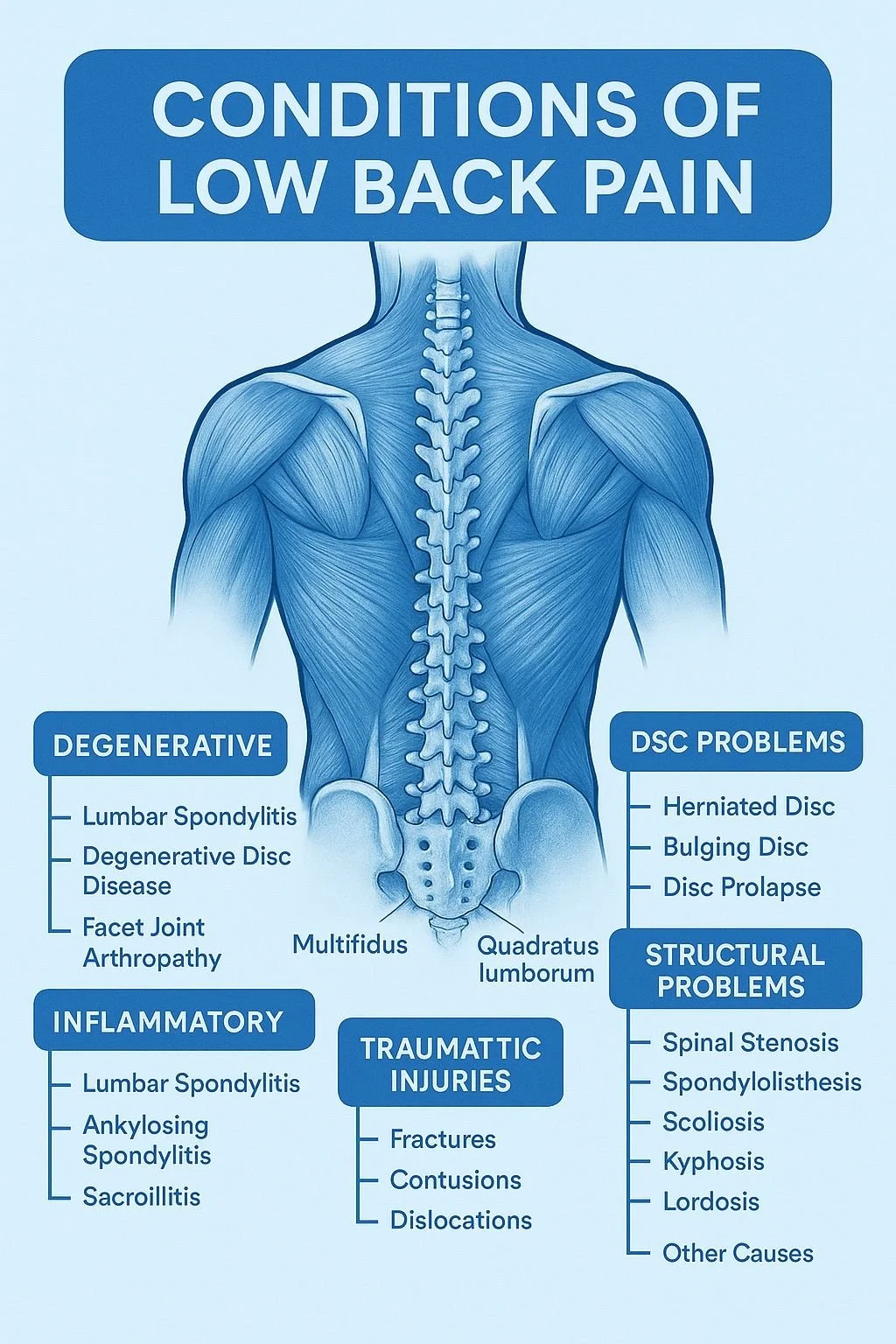

First, although back pain is so common that it is nearly inevitable for every adult to have it at some point in life, the source of the pain can be very different! Here is an excellent infographic I found courtesy of Dr. Zeel Thakker on LinkedIn (Figure 2) that lists just SOME of the possible causes.

(Figure 2)

This figure does not even take into consideration the muscle and nerve issues that are almost a guaranteed aspect of every back pain condition. However, for the purposes of this article, the goal is not to list and understand every possibility and term here, but just to appreciate how many different tissues and structures, not to mention psychological beliefs, can be drivers of pain.

Understanding that pain can be coming from a multitude of sources is very important when it comes to all of your subsequent choices in regards to how you sit, lift things, exercise, and/or rehab.

What really matters:

Although there are many possibilities of causes of back pain, we’ll focus on the few usual suspects that are part of most lower back pain issues.

Back pain often develops as structures of the spine start to break down due to repetitive overloading of compression (think up and down/north and south) and shear (think horizontal/east to west) forces beyond the tolerance levels of the vertebral bodies.

The breakdown of the vertebral bodies often leads to one (or more) of the following:

Disc degeneration issues, which can create nerve impingement and other issues as the discs push out towards your back and can press on the spinal cord and nerve roots.

Bone-related issues, such as fractures of the back part of the vertebrae, which can lead to the vertebrae wanting to move forward which can also put strain on the spinal cord.

Osteoporosis, which is a weakening of the structural integrity of the vertebral body making it more susceptible to collapse.

Stenosis, which is typically an increase in bone formation in the little hole where the individual nerve branches from each level of your spine leave to innervate their respective muscles.

Any and all of these issues will start to affect your muscular system as the body will begin to make compensatory changes to adjust for any spinal instability.

These forces do not act in isolation - you experience both concurrently. However, you can experience higher levels of one vs. the other (typically compression), and based on a specific injury, your spine might tolerate one direction better than another.

So, what really matters when it comes to lifting something up is what YOUR spine can safely tolerate.

At the end of this article, I’ll offer some considerations for lifting, but let’s first get back to that study which examined compression and shear loads in the three different positions: freestyle, squat, and stoop.

Using advanced motion capture and musculoskeletal modeling in 30 healthy individuals lifting a 15 kg box, researchers analyzed continuous and peak compressive, anterior-posterior shear, and total loads relative to body weight. In English: How much stress was being placed vertically down on the spine when lifting; how much stress was being placed horizontally across the spine when lifting; and the total combination of the two. (There is always a combination of horizontal and vertical forces when lifting something up).

Stoop Lifting

Benefits:

Lower total and compressive lumbar loads, particularly in the upper lumbar spine.

Slower lifting speeds reduce strain rates, potentially lowering stress on vertebral discs.

May feel more natural for certain individuals due to less reliance on lower limb strength.

Deficits:

Higher anterior-posterior (AP) shear loads in most lumbar segments, increasing risk in younger individuals with elastic discs.

Greater lumbar flexion may contribute to increased strain on passive spinal structures.

Squat Lifting

Benefits:

Reduces AP shear loads in most segments, including the upper lumbar spine.

Engages lower-body musculature, potentially reducing the load on passive spinal structures.

Keeps lumbar flexion more controlled, though not entirely neutral.

Deficits:

Higher compressive loads in the L5/S1 segment, where herniated discs and spondylolisthesis often occur.

Earlier peak loading in the lifting cycle may increase dynamic forces on the spine.

Requires more energy and lower-limb strength, which can be challenging for certain populations.

Freestyle Lifting

Benefits:

Performed the fastest, which may reduce fatigue during repetitive tasks.

Combines aspects of both stoop and squat, allowing adaptability to the individual's preferences.

Deficits:

Generates higher total spinal loads compared to squat lifting, especially in L5/S1.

More variability in execution could lead to inconsistent spinal loading, increasing injury risk over time.

Let’s do a quick encapsulation:

Freestyle lifting technique had highest TOTAL loads, especially in L5/S1

Squat lifting had highest COMPRESSIVE loads

Stoop lifting had the highest SHEARING loads

Surprising? Yes? No?

Well, either way, let’s now plug back into typical injuries and which posture could be best for each of those:

Disc Herniation

Disc herniation in a vacuum is not a problem. The problem is when the disc (which is integrated into the vertebral bones above and below it) starts to degenerate and then starts to bulge out (NOT slip!) and encroach the nerve roots that are branching out from the spinal cord. Believe it or not, the inside of a spinal disc has concentric rings around the middle (nucleus) just like a tree. When exposed to chronic bending and rotating forces under load, the rings can start to break, letting the nucleus leak out and start pushing the disc outside of its boundary.

Disc herniations happen MOST COMMONLY at the L4/L5 then L5/S1 segments. The most common cause for herniation is REPETITIVE SHEARING FORCES. So, therefore, IF you have, or suspect you have disc herniations, or a condition called spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis (a fracturing of the vertebral bone on the back end of it, then a forward migration of the vertebrae) at those segments, then it could make sense to typically do a squat style lift to avoid irritating those areas, as the other types had an increase in shear force.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is the loss of bone mass, i.e., the structural integrity of the bone, leading it to become more brittle and weaker. Think about this analogy: Take a full can of soda and try to crush it down on top of a table. Then try it with an empty can. Which is easier? Obviously, the loss of mass (in the case of soda liquid volume) makes the structure much easier to deform in an up-and-down direction.

The spine is similar. When there is Osteoporosis, repetitive compressive stresses that are pushing the bones together (like your hand trying to crush the can) can create end plate fractures to the vertebrae, which are fractures on the top or bottom (as opposed to back to front as in spondylolysis). In addition, repetitive compressive stresses can strain the middle of a disc (as opposed to the outer rings) and lead to a reduction of the disc’s height, bringing the vertebrae too close together and reducing the disc’s ability to absorb shock with each step you take. When you damage the nucleus of the disc, the fluids contained inside it push out and start to break those previously mentioned outer layers. So in this case, a STOOP style lift might actually be best to avoid high compressive loads on the lower back!

Spinal stenosis

Spinal stenosis is most aggravated by spinal extension, i.e., straightening your spine as much as you can, in combination with compression. The most common levels that get damaged due to high compressive forces are T12/L1 then L4/L5 and L5/S1. So, if you are someone who has a known condition of spinal stenosis, or a concern about it, it could make sense to adapt a STOOP lift to reduce spinal extension and compressive forces.

No back pain?

Feel free to adopt any posture. Understand that each one has it pros and cons, but having variability in how you lift is actually the most ideal way to move efficiently.

KEEP IN MIND THIS IS ONE STUDY!

While there have been other subsequent published studies that have supported this study, especially in regards to stoop lifting (Schmid, 2024, Dehghan, P., & Arjmand, N. 2024), other studies such as Bazrgari, et al. (2007) and Kingma et al. (2004) have shown less benefit for reduced compression in the lumbar spine in the stoop position.

So, we should choose our posture carefully, but…

Before you get paralysis by analysis, here’s some good news. The spine is actually BUILT to tolerate very high levels of force placed upon it.

Let’s look at some numbers.

From an excellent review by Gallagher and Marras (2012):

The average Ultimate Shear Strength (USS) of human lumbar spines is approximately 1,900 N (427 lbs) for males and 1,700 N (382 lbs) for females. This means the spine can tolerate being exposed to this much load 100 or less times in a day.

For highly repetitive loading (>1,000 cycles/day), loads should not exceed 30% of USS (around 570 N or 128 lbs) to minimize risk.

Of course, having an injury can change all of the above, but spines are strong and resilient. With good muscular strength, spines are capable of withstanding thousands of pounds.

Also, an interesting thing about applying load to the human body is that it is similar to what they say about snake venom: The poison that kills you is also part of the cure the saves you.

What can create damage and injury to a osteoporositic spine? High compressive forces.

What can spur healthy bone remodeling and spinal integrity? You guessed it, high compressive forces.

So it’s not about avoiding anything in particular, it’s about finding the GOLDILOCKS ZONE for just the right amount of load so that it spurs adaptation and then recovery, which leads to stronger, healthier bones over time.

Take Home Messages:

So, here’s the take home. Your body probably already knows which is the best technique for you to adopt! You most likely do it automatically by a process we refer to as self-organization that is a sub-component of a motor control theory called Dynamic Systems Theory (DST) (Kelso, 1995). DST explains how your body processes interactions among the system's elements, such as task demands, space constraints, limb length, speed of movement, muscle force generation, pain signals, body temperature, and others to guide your movement.

To simplify, in other words, your brain is taking in a LOT of information, and then, mainly subconsciously putting together a movement plan, based on all of the resources it has, in order to accomplish the task you are attempting to do in the most efficient manner possible. Sometimes it might “freeze” aka tighten up some muscles around joints to limit how far you can move, sometimes it might be the opposite, as the title implies, our ability to perform any task on any given day is dynamic.

Can you decide override self organization and your body’s instinct to straighten your spine, lift with your legs, etc. when you decide to pick something up? Typically yes, you can voluntarily override just almost any movement. SHOULD you override your subconscious movement strategy? The truth is maybe, maybe not. This is where trying strategies and learning come into play, because, ultimately NO MOVEMENT STRATEGY IS ONE SIZE FITS ALL!

The hard fact is that we all have to be our own investigators and advocates out there in the wild. There are definitely plenty of times where assuming a more rigid posture would be beneficial, however there are an equal amount of times where moving by accepted convention “back straight, lift with your legs” will exacerbate existing issues. The take-home message is not to avoid or demonize squat lifting. The point is that the health advice industry is loaded with outdated research, mistakes, biased opinion, and sadly, blatant misinformation. So, don’t perform a squat lift because it’s the right thing to do, do it because it feels good to you, or you have been advised to do so by a credible medical professional, or you understand your injury status, and this is the best technique for you based on that.

Keep investigating by taking information from quality sources (like this one of course!), run trial and error experiments, and think critically when it comes to digesting any sort of health-related information, like this one of course. :)

References:

Von Arx, M., Liechti, M., Connolly, L., Bangerter, C., Meier, M. L., & Schmid, S. (2021). From stoop to squat: A comprehensive analysis of lumbar loading among different lifting styles. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 9, 769117. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.769117

Dehghan, P., & Arjmand, N. (2024). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Recommended Weight Generates Different Spine Loads in Load-Handling Activity Performed Using Stoop, Semi-squat and Full-Squat Techniques; a Full-Body Musculoskeletal Model Study. Human factors, 66(5), 1387–1398. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187208221141652

Gallagher, S., & Marras, W. S. (2012). Tolerance of the lumbar spine to shear: A review and recommended exposure limits. Clinical Biomechanics, 27(10), 973–978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2012.08.017

Kelso, J. A. S. (1995). Dynamic patterns: The self-organization of brain and behavior. MIT Press.

Schmid, S., Kramers-de Quervain, I., & Baumgartner, W. (2024). Intervertebral disc deformation in the lower lumbar spine during object lifting measured in vivo using indwelling bone pins. Journal of biomechanics, 176, 112352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2024.112352